|

| Social Criticisms of Marketing: High-Pressure Selling |

Shoddy or Unsafe Products

In 1990,

consumer activists declared the Daihatsu Sportrak as 'potentially unstable' and

Suzuki was urged to recall tens of thousands of similar cars. This problem

pales by comparison with that faced by the Ford Pinto, which became the symbol

of automotive disaster when several people died during the 1970s in fuel tank

fires allegedly linked to a design fault,. More recently, Chrysler issued one

of the largest product recall notices in the history of the motoring industry,

calling back 900,000 vehicles, ranging from pick-ups to a selection of 'people

carriers' including the Voyager, Wrangler, and Jeep Cherokee models, for a

variety of reasons in seven different recalls. One of the biggest recalls in

1997, according to figures from the British vehicle inspectorate, was one

undertaken by V\V, asking 150.000 Golf and Vento saloon owners to have their

cars checked for wiring faults. In 1996, VW also recalled 350,000 of its models

worldwide because of a potentially faulty electric cable, as well as some

950,000 Golfs, Jettas, Passats, and Corrados because of problems, including a

cooling system fault, which could potentially damage engines and injure

passengers. Early in 1997, Vauxhall called in more than 39,000 Veetras to check

loose fuel pipes. Even Rolls-Royce was forced to check some of its Bentley

Continental T sports coupes (at £220,000 apiece) because of concerns that.t

airbags were firing unexpectedly

For years

now, consumer protection groups or associations in many countries have

regularly tested products for safety, and have reported hazards found in tested

products, such as electrical dangers in appliances, and injury risks from lawnmowers and faulty car design. The testing and reporting activities of these

organizations have helped consumers make better buying decisions and have

encouraged businesses to eliminate product flaws. Marketers may sometimes face

dilemmas when seeking to balance consumer needs and ethical eon si decorations.

For example, no amount of test results can guarantee product safety in cars if

consumers value speed and power more than safety features. Buyers might choose

a less expensive chain saw without a safety guard, although society or a

government regulatory agency might deem it irresponsible and unethical for the

manufacturer to sell it. However, most responsible manufacturers want to produce

quality goods. The way a company deals with product quality and safety problems

can damage or help its reputation. Companies selling poor-quality or unsafe

products risk damaging conflicts with consumer groups. Moreover, unsafe

products can result in product liability suits and large awards for damages.

Consumers who are unhappy with a firm's products may avoid its other products

and talk other consumers into doing the same. More fundamentally, today's

marketers know that self-imposed, high ethical standards, which accompany

customer-driven quality, result in customer satisfaction, which in turn creates

profitable customer relationships.

Planned Obsolescence'

Critics

have charged that some producers follow a program of planned obsolescence.

causing their products to become obsolete before they need replacement. In many

cases, producers have been accused of continually changing consumer concepts of

acceptable styles in order to encourage more and earlier buying. An obvious

example is constantly changing clothing fashions. Producers have also been

accused of holding back attractive functional features, then introducing them

later to make older models obsolete. Critics claim that this practice is

frequently found in the consumer electronics and computer industry. The

Japanese camera, watch, and consumer electronics companies frustrate consumers

because a rapid and frequent model replacement has created difficulties in

obtaining spare parts for old models; dealers refuse to repair outdated models, and planned obsolescence rapidly erodes basic product values. Finally,

producers have been accused of using materials and components that will break,

wear, rust or rot sooner than they should. For example, many drapery

manufacturers are using a higher percentage of rayon in their curtains. They

argue that rayon reduces the price of curtains and has better-holding

power. Critics claim that using more rayon causes the curtains to fall apart

sooner. European consumers have also found, to their annoyance, how rapidly certain

European brands of toasters rust - for an appliance that rarely gets into

contact with water, this is an amazing technological feat! Marketers respond

that consumers like style changes; they get tired of the old goods and want a

new look in fashion or a new design in cars. No one has to buy the new look,

and if too few people like it. it will simply fail. Companies frequently

withhold new features when they are not fully tested when they add more cost

to the product than consumers are willing to pay and for other good reasons.

But they do so at the risk that a competitor will introduce the new feature and

steal the market. Moreover, companies often put in new materials to lower their

costs and prices. They do not design their products to break down earlier,

because they do not want to lose their customers to other brands. Thus, much

so-called planned obsolescence is the working of the competitive and

technological forces in a free society - forces that lead to ever-improving

goods and services.

Planned

obsolescence A strategy of causing products to become obsolete before they

actually, need a replacement

Poor Service to Disadvantaged Consumers

Finally, marketing has been accused of

poorly serving disadvantaged consumers. Critics claim that the urban poor often

has to shop in smaller stores that carry interior goods and charge higher

prices. Marketing's eye on profits also means that disadvantaged consumers are

not viable segments to target. The high-income consumer is the preferred

target. Clearly, better marketing systems must be built in low-income areas -

one hope is to get large retailers to open outlets in low-income areas.

Moreover, low-income people clearly need consumer protection. Consumer-protection

agencies should take action against suppliers who advertise false values, sell

old merchandise as new, or charge too much for credit. Offenders who deliver poor value should be expected to compensate customers, as in the case of many

UK pension providers, who were required to meet mis-spelling compensation

targets following the disclosure of malpractices by an Office of Fair Trading

(OFT) investigation. We now turn to social critics' assessment of how marketing

affects society as a whole

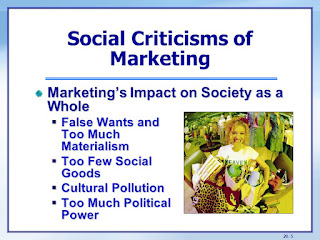

Marketing's

Impact on Society as a Whole

The

marketing system as we - in Europe and other developed economies outside North

America — are experiencing it, has been accused of adding to several 'evils' in

our society at large. Advertising has been a special target. It has been blamed

for creating false wants, nurturing greedy aspirations, and inculcating too much

materialism in our society

False Wants and Too Much Materialism

Critics have charged that, in advanced

nations such as the USA, the marketing system urges too much interest in

material possessions. People are judged by what they own rather than by what

they ore. To be considered successful, people must own a smart-looking house or

apartment in a prime residential site, expensive cars, and the latest designer-label clothes and consumer electronics. Consider, for example, the

training-shoe market. These days, training shoes have gone the same way as

cameras, watches, and mobile phones: functionality is useless without 'tec

lino-supremacy' and high style. Take Nike's Air Max Tailwind which features:

'Flexi-laces' which stretch to give foot comfort; 'interactive eye stay for

one-movement tightening and adjusting; 'mesh upper' made of lightweight

synthetic leather for cooler feet; 'plastic air pockets' filled with sulfur

hexafluoride for added cushioning; 'flexible grooves' in the arch of the shoe

to allow natural foot movements and give support and 'waffle soles' with

grooved treads for traction and support! So sophisticated has it become that it

is no longer even enough to say that you have a pair of Nikes. Its famous tick the logo is now more globally visible than the crucifix, so your Nikes had better

be a very rare variety and/or very expensive if you expect to seriously

impress, Alternatively, you could go for a limited edition Adidas or something

slightly underground like DC skate shoes

Is there a similar enchantment with money

in Europe? Asia? The rest of the world? It is neither feasible nor appropriate

for this chapter to indulge readers in an extensive debate on cross-cultural

similarities and dissimilarities in materialistic tendencies and behavior, and

whether marketing is the root cause of these desires. Rather, we acknowledge the

phenomenon of the 'yuppie generation' that emerged in the 1980s, symbolizing a

new materialistic culture that looked certain to stay. In the 1990s, although

many social scientists noted a reaction against the opulence and waste of The 1980s and a return to more basic values and social commitment, our infatuation

with material things continues.

For example, when asked in a recent poll what

they value most in their lives, subjects listed enjoyable work (86 percent),

happy children (84 percent), a good marriage (69 percent), and contributions

to society (66 percent). However, when asked what most symbolizes success, 85

percent said money and the things it will buy.7 Critics view this interest in

material things not as a natural state of mind, but rather as a matter of false

wants created by marketing. Businesses stimulate people's desires for goods

through the force of advertising, and advertisers use the mass media to create

materialistic models of the good life. People work harder to earn the necessary

money. Their purchases increase the output of the nation's industry, and the industry, in turn, uses the advertising media to stimulate more desire for its

industrial output. Thus marketing is seen as creating false wants that benefit the industry more than they benefit consumers. However, these criticisms overstate

the power of businesses to create needs. People have strong defenses against

advertising and other marketing tools. Marketers are most effective when they

appeal to existing wants rather than when they attempt to create new ones.

Furthermore, people seek information when making important purchases and often

do not rely on single sources. Consumers ultimately display rational buying

behavior: even minor purchases that may be affected by advertising messages lead

to repeat purchases only if the product performs as promised. Finally, the high

failure rate of new products shows that companies are not always able to

control demand. On a deeper level, our wants and values are influenced not only

by marketers, but also by family, peer groups, religion, ethnic background, and

education. If societies are highly materialistic, these values arose out of

basic socialization processes that go much deeper than business and mass media

could produce alone. The importance of wealth and material possessions to the

overseas Chinese, for example, is explained more by cultural and socialization

factors than by sustained exposure to Western advertising influences.

Too Few Social Goods

The business has been accused of overselling

private goods at the expense of public goods. As private goods increase, they

require more public services that are usually not forthcoming. For example, an

increase in car ownership (private good) requires more roads, traffic control,

parking spaces, and police services (public goods). The overselling of private

goods results in 'social costs. For cars, the social costs include excessive

traffic congestion, air pollution, and deaths and injuries from car accidents.

A way must be found to restore a balance between private and arid and public goods. One

option is to make producers bear the full social costs of their operations. For

example, the government could require car manufacturers to build cars with

additional safety features and better pollution-control systems. Carmakers

would then raise their prices to cover extra costs. If buyers found the price

of some cars too high, however, the producers of these cars would disappear,

and demand would move to those producers that could support both the private

and social costs.

Cultural Pollution

Critics charge the marketing system with creating cultural pollution. Our senses are being assaulted constantly by advertising. Commercials interrupt serious programs; pages of ads obscure printed matter; billboards mar beautiful scenery. These interruptions continuously pollute people's minds with messages of materialism, sex, power, or status. Although most people do not find advertising overly annoying (some even think it is the best part of television programming), some critics call for sweeping changes. Marketers answer die charges of 'commercial noise' with the following arguments. First, they hope that their ads reach primarily the target audience. But because of mass-communication channels, some ads are bound to reach people who have no interest in the product and are therefore bored or annoyed. People who buy magazines slanted towards their interests - such as Vogue or Fortune - rarely complain about the ads because the magazines advertise products of interest. Second, ads make much of television and radio free and keep down the costs of magazines and newspapers. Most people think commercials are a small price to pay for these benefits.

Too Much Political Power

Another criticism is that business wields

too much political power. 'Oil', 'tobacco', • pharmaceuticals, 'financial

services, and 'alcohol' have the support of important politicians and civil

servants, who look after an industry's interests against the public interest.

Advertisers are accused of holding too much power over the mass media, limiting

their freedom to report independently and objectively. The setting up of

citizens' charters and greater concern for consumer rights and protection in

the 1990s will see improvements, not regression, in business accountability. Fortunately,

many powerful business interests once thought to be untouchable have been tamed

in the public interest. For example, in the United States, Ralph Nader, a consumerism campaigner, caused legislation that forced the car industry to

build more safety into its cars, and the Surgeon General's Report resulted in

cigarette companies putting health warnings on their packages. Moreover,

because the media receive advertising revenues from many different advertisers,

it is easier to resist the influence of one or a few of them. Too much business

power tends to result in counterforces that check and offset these powerful

interests. Let us now take a look at the criticisms that business critics have

leveled at companies' marketing practices.

Think your

friends would be interested? Share this story!

( Keywords )

Post a Comment