|

| The color purple: Alice Walker: Chapter 12 |

Remember the

main street of town? I asked. Remember the hitching post in front of Finley’s

dry goods store? Remember how the store smelled like peanut shells?

She says she

remembers all this, but no men speaking to her.

Then I

remember her quilts. The Olinka men make beautiful quilts that are full of

animals and birds and people. And as soon as Corrine saw them, she began to

make a quilt that alternated one square of appliqued figures with one

nine-patch block, using the clothes the children had outgrown, and some of her

old dresses.

I went to her

trunk and started hauling out quilts. Don’t touch my things, said Corrine. I’m

not gone yet.

I held up the first one and then another to the light, trying to find the first one I

remembered her making. And trying to remember, at the same time, the dresses

she and Olivia were wearing the first months I lived with them.

Aha, I said,

when I found what I was looking for, and laid the quilt across the bed.

Do you

remember buying this cloth? I asked, pointing to a flowered square. And what

about this checkered bird? She traced the patterns with her finger, and slowly

her eyes filled with tears.

She was so

much like Olivia! she said. I was afraid she’d want her back. So I forgot her

as soon as I could. All I let myself think about was how the clerk treated me!

I was acting like somebody because I was Samuel’s wife and a Spelman Seminary

graduate, and he treated me like any ordinary person. Oh, my feelings were

hurt! And I was mad! And that’s what I thought about, even told Samuel about,

on the way home. Not about your sister—what was her name?—Celie? Nothing about

her.

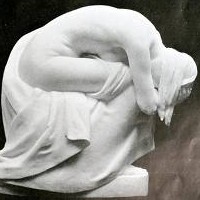

She began to

cry in earnest. Me and Samuel holding her hands.

Don’t cry.

Don’t cry, I said. My sister was glad to see Olivia with you. Glad to see her

alive. She thought both her children were dead.

Poor thing!

said, Samuel. And we sat there talking a little and holding on to each other

until Corrine fell off to sleep. But, Celie, in the middle of the night woke

up, turned to Samuel, and said: I believe. And died anyway.

Your Sister in Sorrow, Nettie

Just when I think I’ve learned to live

with the heat, the constant dampness, even the steaminess of my clothes, the

swampiness under my arms and between my legs, my friend comes. And cramps and

aches and pains—but I must still keep going as if nothing is happening, or be

an embarrassment to Samuel, the children, and myself. Not to mention the

villagers, who think women who have their friends should not even be seen.

Right after her mother’s death, Olivia

got her friend; she and Tashi tend to each other is my guess.

Nothing is said to me, in any event, and I don’t know how to bring the subject

up. This feels wrong to me; but if you talk to an Olinka girl about her private

parts, her mother and father will be annoyed, and it is very important to

Olivia not to be looked upon as an outsider. Although the one ritual they do

have to celebrate womanhood is so bloody and painful, I forbid Olivia to even

think about it.

Do you remember how scared I was when it

first happened to me? I thought I had cut myself. But thank God you were there

to tell me I was all right.

We buried Corrine in the Olinka way,

wrapped in barkcloth under a large tree. All of her sweet ways went with her.

All of her education and heart were intent on doing good. She taught me so

much! I know I will miss her always. The children were stunned by their

mother’s death. They knew she was very sick, but death is not something they

think about in relation to their parents or themselves. It was a strange little

procession. All of us in our white robes and with our faces painted white.

Samuel is like someone lost. I don’t believe they’ve spent a night apart since

their marriage.

And how are you? dear, Sister. The years

have come and gone without a single word from you. Only the sky above us do we

hold in common. I look at it often as if, somehow, reflected from its

immensities, I will one day find myself gazing into your eyes. Your dear,

large, clean, and beautiful eyes. Oh, Celie! My life here is nothing but work,

work, work, and worry. What girlhood I might have had passed me by. And I have

nothing of my own. No man, no children, no close friend, except for Samuel. But

I do have children, Adam and Olivia. And I do have

friends, Tashi and Catherine. I even have a family—this village, which has

fallen on such hard times.

Now the engineers have come to inspect the

territory. Two white men came yesterday and spent a couple of hours strolling

about the village, mainly looking at the wells. Such is the innate politeness

of the Olinka that they rushed about preparing food for them, though precious

little is left since many of the gardens that flourish at this time of the year

have been destroyed. And the white men sat eating as if the food was beneath

notice.

It is understood by the Olinka that

nothing good is likely to come from the same persons who destroyed their

houses, but custom dies hard. I did not speak to the men myself, but Samuel

did. He said their talk was all of the workers, kilometers of land, rainfall,

seedlings, machinery, and whatnot. One seemed totally indifferent to the people

around him—simply eating and then smoking and staring off into the distance—and

the other, somewhat younger, appeared to be enthusiastic about learning the

language. Before, he says, it dies out.

I did not enjoy watching Samuel speaking

to either of them. The one who hung on every word, or the one who looked

through Samuel’s head.

Samuel gave me all of Corrine’s clothes,

and I need them, though none of our clothing is suitable for this climate. This

is true even of the clothing the Africans wear. They used to wear very little,

but the ladies of England introduced the Mother Hubbard, a long, cumbersome,

ill-fitting dress, completely shapeless, that inevitably gets dragged in the

fire, causing burns aplenty. I have never been able to bring myself to wear one

of these dresses, which all seem to have been made with giants in mind, so I

was glad to have Corrine’s things. At the same time, I dreaded putting them on.

I remembered her saying we should stop wearing each other’s clothes. And the

memory pained me.

Are you sure Sister Corrine would want

this? I asked Samuel.

Yes, Sister Nettie, he said. Try not to

hold her fears against her. In the end, she understood and believed. And

forgave—whatever there was to forgive.

I should have said something sooner, I

said.

He asked me to tell him about you, and the

words poured out like water. I was dying to tell someone about us. I told him

about my letters to you every Christmas and Easter, and about how much it would

have meant to us if he had gone to see you after I left. He was sorry he

hesitated to become involved.

If only I’d understood then what I know

now! he said.

But how could he? There is so much we

don’t understand. And so much unhappiness comes because of that.

love and Merry Christmas

to you, Your sister, Nettie

I don’t write to God anymore. I write to you. What

happens to God? ask Shug.

Who that? I say.

She looks at me seriously.

Big a devil as you is, I say, you not worried bout no

God, surely.

She says, Waits a minute. Hold on just a minute here.

Just because I don’t harass it as some peoples know don’t mean I ain’t got

religion.

What does God do for me? I asked.

She says, Celie! Like she was shocked. He gave you

life, good health, and a good woman that loves you to death.

Yeah, I say, and he gives me a lynched daddy, a crazy

mama, a lowdown dog of a step-pa, and a sister I probably won’t ever see again.

Anyhow, I say, the God I have been praying and writing to is a man. And act

just like all the other men I know. Trifling, forgetful, and lowdown.

She says, Miss Celie, You better hush. God might hear

you.

Let ‘im hear me, I say. If he ever listened to poor

colored women the world would be a different place, I can tell you. She talks

and she talks, trying to budge my way from blasphemy. But I blaspheme much as I

want to.

All my life I never care what people thought bout

anything I did, I say. But deep in my heart, I care about God. What is he going

to think? And come to find out, he doesn’t think. Just sit up there glorying in

being deaf, I reckon. But it ain’t easy, trying to do without God. Even if you

know he ain’t there, trying to do without him is a strain.

I am a sinner, says Shug. Cause I was born. I don’t

deny it. But once you find out what’s out there waiting for us, what else can

you be?

Sinners have more good times, I say. Do you know why?

she asked.

Cause you ain’t all the time worrying bout God, I say.

Now, that ain’t it, she says. We worry bout God a lot.

But once we feel loved by God, we do the best we can to please him with what we

like.

You telling me God loves you, and you ain’t never done

nothing for him? I mean, not go to church, sing in the choir, feed the

preacher, and all like that?

But if God loves me, Celie, I don’t have to do all

that. Unless I want to. There are a lot of other things I can do that I speck God

likes.

Like what? I asked.

Oh, she says. I can lay back and just admire stuff. Be

happy. Have a good time. Well, this sounds like blasphemy sure Nuff.

She says, Celie, tell the truth, have you ever found

God in church? I never did. I just found a bunch of folks hoping for him to

show. Any God I ever felt in church I brought in with me. And I think all the

other folks did too. They come to church to share God, not find God.

Some folks didn’t have him to share, I said. They were

the ones who didn’t speak to me while I was there struggling with my big belly

and Mr. Children.

Right, she says.

Then she says: Tell me what your God looks like, Celie.

Aw now, I say. I’m too shame. Nobody ever asked me

this before, so I’m sort of taken by surprise. Besides, when I think about it,

it doesn’t seem quite right. But it's all I got. I decide to stick up for him,

just to see what Shug says.

Okay, I say. He is big and old and tall and

gray-bearded and white. He wears white robes and goes barefooted. Blue eyes?

she asked.

Sort of bluish-gray. Cool. Big though. White lashes. I

say. She laughs.

Why do you laugh? I asked. I don’t think it is so

funny. What do you expect him to look like, Mr.?

That wouldn’t be any improvement, she says. Then she

tell me this old white man is the same God she used to see when she prayed. If

you wait to find God in church, Celie, she say, that’s who is bound to show up,

'cause that’s where he lives.

How come? I asked.

Cause that’s the one that’s in the white folks’ white

bible.

Shug! I say. God wrote the bible, and white folks had

nothing to do with it.

How come he looks just like them, then? she says. Only bigger? And a heap more hair. How come the bible just like everything else they make, is all about them doing one thing and another, and all the colored folks doing is getting cursed

I never

thought bout that.

Nettie

says somewhere in the bible says Jesus’ hair was like lamb’s wool, I say.

Well, say

Shug, if he came to any of these churches we talking bout he’d have to have it

conked before anybody paid him any attention. The last thing my people want to

think about their God is that his hair is kinky.

That’s the

truth, I say.

Ain’t no

way to read the bible and not think God white, she says. Then she sighs. When I

found out I thought God was white, and a man, I lost interest. You're mad cause

he doesn’t seem to listen to your prayers. Humph! Does the mayor listen to

anything Color says? Ask Sofia, she says.

But I

don’t have toast Sofia. I know white people never listen to colored, period. If

they do, they only listen long enough to be able to tell you what to do.

Here’s the

thing, says Shug. The thing I believe. God is inside you and everybody else. You

come into the world with God. But only those that search for it inside find it.

And sometimes it just manifests itself even if you not looking, or don’t know

what you looking for. Trouble doing it for most folks, I think. Sorrow, lord.

Feeling like shit.

It? I

asked.

Yeah, It.

God ain’t he or she, but an It. But what does it look like? I asked.

Don’t look

like anything, she said. It ain’t a picture show. It ain’t something you can

look at apart from anything else, including yourself. I believe God is

everything, says Shug. Everything that is or ever was or ever will be. And when

you can feel that, and be happy to feel that, you’ve found It.

Shug a

beautiful something, let me tell you. She frowns a little, looks out across the

yard, and leans back in her chair, looking like a big rose.

She says,

My first step from the old white man was trees. Then air. Then birds. Then

other people. But one day when I was sitting quietly and feeling like a

motherless child, which I was, it come to me: that feeling of being part of

everything, not separate at all. I knew that if I cut a tree, my arm would

bleed. And I laughed and I cried and I run all around the house. I knew just

what it was. When it happens, you can’t miss it. It's sort of like you know

what, she says, grinning and rubbing high up on my thigh.

Shug! I say.

Oh, she

says. God loves all their feelings. That’s some of the best stuff God did. And

when you know God loves ’em you enjoy ’em a lot more. You can just relax, go

with everything that’s going on, and praise God by liking what you like.

God

doesn’t think it dirty? I asked.

Now, she

says. God made it. Listen, God loves everything you love—and a mess of stuff you

don’t. But more than anything else, God loves admiration.

Are you

saying God is vain? I asked

Naw, she

says. Not vain, just want to share a good thing. I think it pisses God off

if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don’t notice it.

What does

it do when it is pissed off? I asked.

Oh, it

makes something else. People think pleasing God is all God cares about. But any

fool living in the world can see it always trying to please us back.

Yeah? I

say.

Yeah, she

says. It always makes little surprises and springs them on us when we least

expect them. You mean it wants to be loved, just like the bible says.

Yes,

Celie, she says. Everything wants to be loved. We sing and dance, make faces,

and give flower bouquets, trying to be loved. Have you ever noticed that trees

do everything to get the attention we do, except walk?

Well, we

talk and talk bout God, but I’m still adrift.

Trying to

chase that old white man out of my head. I have been so busy thinking bout him that I never truly notice anything God makes. Not a blade of corn (how does it do

that?) not the color purple (where it come from?). Not the little wildflowers.

Nothing.

Now that

my eyes are open, I feel like a fool. Next to any little scrub of a bush in my

yard, Mr.’s evil sort of shrink. But not altogether. Still, it is like Shug

says, You have to get a man off your eyeball before you can see anything at all.

Man

corrupts everything, says Shug. He is on your box of grits, in your head, and all

over the radio. He tries to make you think he is everywhere. Soon as you think

he is everywhere, you think he is God. But he ain’t. Whenever you trying to

pray, and man plops himself on the other end of it, tell him to get lost, say

Shug. Conjure up flowers, wind, water, and a big rock.

But this hard

work, let me tell you. He's been there so long, he won't want to budge. He

threatens lightning, floods, and earthquakes. Our fight. I hardly pray at all.

Every time I conjure up a rock, I throw it.

Amen

When I told Shug I’m writing to you

instead of to God, she laugh. Nettie doesn’t know these people, she says.

Considering who I have been writing to, this strikes me funny.

It was Sofia you saw working as the

mayor’s maid. The woman you saw carrying the white woman’s packages that day in

town. Sofia Mr.’s son Harpo’s wife. Police lock her up for sassing the mayor’s

wife and hitting the mayor back. First, she was in prison working in the

laundry and dying fast. Then we got her to move to the mayor’s house. She had to

sleep in a little room up under the house, but it was better than prison.

Flies, maybe, but no rats.

Anyhow, they kept her for eleven and a half

years, giving her six months off for good behavior so she could come home early

to her family. Her bigger children are married and gone, and her littlest

children are mad at her, don’t know who she is. Think she acts funny, looks

old, and dotes on that little white gal she raises.

Yesterday we all had dinner at Odessa’s

house. Odessa Sofia’s sister. She raises the kids. Her and her husband Jack. Harpo’s

woman Squeak, and Harpo himself.

Sofia sits down at the big table like

there’s no room for her. Children reach across her like she is not there. Harpo

and Squeak act like an old married couple. Children call Odessa mama. Call

Squeak little mama. Call Sofia “Miss.” The only one who seems to pay her any

attention at all is Harpo and Squeak’s little girl, Suzie Q. She sits across

from Sofia and squinches up her eyes at her. As soon as dinner was over, Shug

push back her chair and light a cigarette. Now is come the time to tell yall,

she says.

Tell us what? Harpo asked.

Us leaving, she says.

Yeah? Say Harpo, looking around for the

coffee. And then looking over at Grady.

Us leaving, Shug says again. Mr. Look is struck like he always looks when Shug says she going anywhere. He reaches down

and rubs his stomach, looking offside her head like nothing has been said.

Grady says, Such good people, that’s the

truth. The salt of the earth. But—time to move on.

Squeak not saying anything. She got her

chin glued to her plate. I’m not saying anything either. I’m waiting for the

feathers to fly.

Celie is coming with us, says Shug.

Mr.’s head swivels back straight. Say

what? he asked. Celie is coming to Memphis with me.

Over my dead body, Mr. says.

You satisfied that what you want, Shug

says, cool as clabber.

Mr. starts up from his

seat, looks at Shug, and plops back down again. He looks over at me. I thought you

were finally happy, he say. What's wrong now?

You a lowdown dog is what’s wrong, I say.

It’s time to leave you and enter into the Creation. And your dead body is just

the welcome mat I need.

Say what? he asked. Shock.

All around the table folks' mouths be

dropping open.

You took my sister Nettie away from me, I

say. And she was the only person who love me in the world. Mr. starts to

sputter. But. Sound like some kind of motor.

But Nettie and my children coming home

soon, I say. And when she does, call us together gon whup your ass. Nettie and

your children! Say Mr. Are you talking crazy.

I got children, I say. Being brought up in

Africa. Good schools, lots of fresh air and exercise. Turning out a heap better

than the fools you didn’t even try to raise.

Hold on, say Harpo.

Oh, hold on hell, I say. If you hadn’t

tried to rule over Sofia the white folks never would have caught her. Sofia was

so surprised to hear me speak up that she ain’t chewed for ten minutes.

That’s a lie, says Harpo.

A little truth in it, says Sofia.

Everybody looks at her like they are

surprised she is there. It is like a voice speaking from the grave.

You were all rotten children, I say. You

made my life hell on earth. And your daddy here ain’t dead horse’s shit. Mr. reaches over

to slap me. I jab my case knife in his hand.

You bitch, he says. What will people say,

you running off to Memphis like you don’t have a house to look after?

Shug says, Albert. Try to think like you

got some sense. Why any woman gives a shit what people think is a mystery to

me. Well, say, Grady, trying to bring light. A woman can’t get a man if people

talk.

Shug looks at me and we giggle. Then we laugh sure Nuff. Then Squeak starts to laugh. Then Sofia. All of us laugh and laugh. Shug says, Ain’t they something? We say um hum, and slap the table, wiping the water from our eyes.

Harpo looks at Squeak. Shut up Squeak, he

says. It is bad luck for women to laugh at men. She says, Okay. She sits up

straight, sucks in her breath, and tries to press her face together.

He looks at Sofia. She looks at him and

laughs in his face. I already had my bad luck, she says. I had enough to keep me

laughing for the rest of my life.

Harpo looks at her like he did the night

she knock Mary Agnes down. A little spark flies across the table. I got six

children by this crazy woman, he mutters.

Five, she says.

He outdid he can’t even say, Say what?

He looks over at the youngest child. She

is sullen, mean, mischievous, and too stubborn to live in this world. But he

loves her best of all. Her name is Henrietta.

Henrietta, he says.

She says, Yesssss ... as they say it on

the radio.

Everything she says confuses him. Nothing,

he says. Then he says, Goes get me a cool glass of water. She doesn’t move.

Please, he says.

She goes git the water, puts it by his

plate, and gives him a peck on the cheek. Say, Poor Daddy. Sit back down. You not

getting a penny of my money, Mr. says to me. Not one thin

dime.

Did I ever ask you for money? I say. I

never ask you for anything. Not even for your sorry hand in marriage.

Shug break in right there. Wait, she says.

Hold it. Somebody else going with us too. No use in Celie being the only one

taking the weight.

Everybody sort of cut their eyes at Sofia.

She is the one they can’t quite find a place for. She was the stranger.

It ain’t me, she says, and her look-say, Fuck

you for entertaining the thought. She reaches for a biscuit and sort of roots

her behind deeper into her seat. One look at this big stout graying, wild-eyed

woman and you know not even toast. Nothing. But just to clear this up neat and

quick, she said, I’m home. Period.

Her sister Odessa comes and put her arms

around her. Jack moves up close. Course you are, Jack says.

Mama crying? ask one of Sofia's children.

Miss Sofia too, another one says.

But Sofia cries quickly like she does most

things. Who going? she asked.

Nobody says anything. It is so quiet you

can hear the embers dying back in the stove. Sound like they falling in on each

other. Finally, Squeak looks at everybody from under her bangs. Me, she says.

I’m going North.

Are you going What? say Harpo. He was so

surprised. He begins to sputter, sputter, just like his daddy. Sound like I

don’t know what. I want to sing, say Squeak.

Sing! Say Harpo.

Yeah, say Squeak. Sing. I ain’t sung in

public since Jolentha was born. Her name is Jolentha. They call her Suzie Q.

You ain’t had to sing in public since Jolentha was born. Everything you need I

done provided for.

I need to sing, say Squeak.

Listen Squeak, say Harpo. You can’t go to

Memphis. That’s all there is to it. Mary Agnes, say Squeak.

Squeak, Mary Agnes, what difference does it

make?

It makes a lot, says Squeak. When I was

Mary Agnes I could sing in public. Just then a little knock comes on the door.

Odessa and Jack look at each other. Come

in, says, Jack.

A skinny little white woman sticks most of

herself through the door. Oh, you all are eating dinner, she says. Excuse me.

That’s all right, says Odessa. Us just

finishing up. But there’s plenty left. Why don’t you sit down and join us? Or I

could fix you something to eat on the porch.

Oh lord, say Shug.

was Eleanor Jane, the white girl Sofia used

to work for.

She looks around till she spots Sofia,

then she seems to let her breath out. No thank you, Odessa, she says. I ain’t

hungry. I just come to see Sofia.

Sofia, she says. Can I see you on the

porch for a minute?

All right, Miss Eleanor, she says. Sofia

pushes back from the table and they go out on the porch. A few minutes later we

hear Miss Eleanor sniffling. Then she boo-hoo.

What the matter with her? Mr. ask.

Henrietta says, Prob-limbszzzz... like

somebody on the radio.

Odessa shrug.

She is always underfoot, she says.

A lot of

drinking in that family, said, Jack. Plus, they can’t keep that boy of theirs

in college. He gets drunk, aggravates his sister, chases women, hunts my people,

and that ain’t all.

That's enough,

says Shug. Poor Sofia.

Pretty soon

Sofia comes back in and sits down. What the matter? ask Odessa.

A lot of mess

back at the house says Sofia. Did you get to go back up there? Odessa asked.

Yeah, say

Sofia. In a few minutes. But I’ll try to be back before the children go to bed.

Henrietta ask to be excused, saying she got a stomach ache.

Squeak and

Harpo’s little girl come over, look up at Sofia, and say, You gotta go Misofia?

Sofia says, Yeah, pull her up on her lap. Sofia is on parole, she says. Got to

act nice.

Suzie Q lay

her head on Sofia's chest. Poor Sofia, she says, just like she heard Shug. Poor

Sofia. Mary Agnes, darling, say Harpo, look how Suzie Q take to Sofia.

Yeah, say

Squeak, children know good when they see it. She and Sofia smile at one

another. Go on sing, say Sofia, I’ll look after this one till you come back.

You will? say

Squeak.

Yeah, say

Sofia.

And look after

Harpo, too, says Squeak. Please, ma’am.

Amen

Think your

friends would be interested? Share this story!

( Keywords )

Post a Comment